There was a good example of “legal culture,” said Lateran Pontiff University professor Matteo Nucci, presenting at a press conference, one of the many conferences in Rome these days, on the Lateran Treaty between Pope Pius 11th and the fascist regime of Benito Mussolini, signed on 11 February 1929.

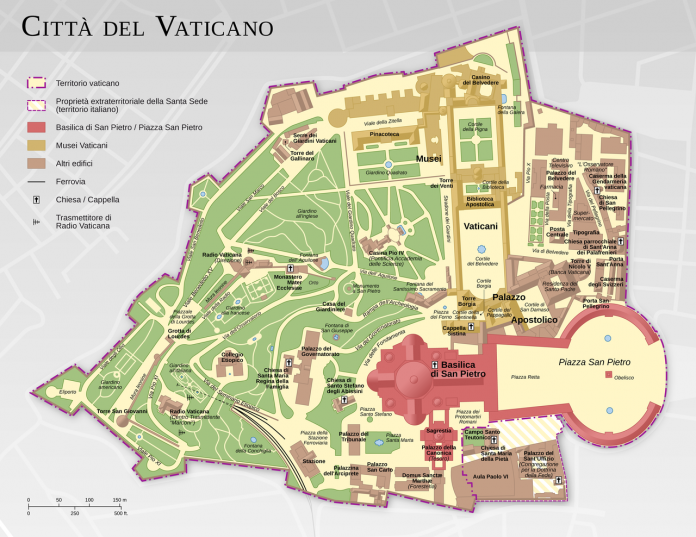

The Treaty solved the “Roman question”. It officially established the abolition of the Pontiff state, which had ceased to exist after the capture of Rome by the forces of Giuseppe Garibaldi on 20 September 1870, cleared the relations, at international law level, between the Italian state and the Holy See, formalised the relationship of the Catholic faith with the Italian State, founded the Vatican City State (at 0.44 square kilometres with 389 Italian nationals and 113 Swiss guards) and indemnified the Holy See with Lit 1.75bn in cash and in securities of the Italian State, as compensation for the abolition of the Pontifical State.

What was happening between 1870 and 1929? The Popes believed the Church was under persecution and they were self-contained within the papal buildings. Several attempts to resolve the crisis and to achieve the official union of the Italian lands into a single state had taken place over the course of 59 years. In that period, the Holy See continued of course to play the international role that had historically belonged to it.

The catalyst for accelerating reciprocal concessions was the Italian refusal to participate in the summit after the end of the First World War.

Of course, the deal did not solve all the problems of the relations between the Holy See and the fascist government. There have been many tensions, related to the interpretation of the Treaty, to the possibility of activating the Catholic Action which was opposed to the fascist organisations of the regime, for the implementation of the embarrassing racial laws promulgated from 1938 to 1943.

Italy’s great politician Alcide de Gasperi said referring to the Treaty that: “The result seems to be a victory for the regime but, historically, it is a liberation of the church and a success for the Italian nation”.

De Gasperi, the leader of the Christian Democrats, with the agreement of Italian Communist Party, but not of the rest of the liberal and leftist powers of the country, succeeded in introducing the agreement into the Italian Constitution of 1947.

The Treaty was revised in 1984, and the Concordate was signed by the then Bettino Craxi’s government with the Vatican Secretary of State Cardinal Augustine Casaroli. Among the most popular changes were the optional choice of religious lessons at school and the agreement to pay eight per thousand of the Italians’ income for religious and charitable work to the body they choose: the corresponding money is given to the religious communities of the country (not only the Catholics) and go on enhancing the clergy and the activities of the church.

It is obvious that the Holy See, historically, considers acceptance of the new reality in 1929 to be the acceptance of the “signs of the times”.

The Holy See has shown forethought and wisdom in the Light of the Gospel, with the aim, liberated by the earthly bonds (such as the papal lands) but with a minimum of legal security (maintaining his independence as self-governing within a minimal territorial region) to continue to have International Presence and Intervention, not only for the faithful but for all people in difficulties, regardless of race and religion.

In the difficult times we live, a calm voice, against populism and for the defence of the weak, such as the Holy See, under a charismatic Pope, such as Francis, is very useful.

The recent visit of the Pope in the United Arab Emirates was a proof of this.

Dimitris Levantis is a Lawyer and Member of the Synodal Committee “Justice and Peace”