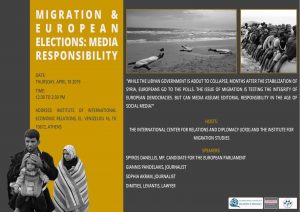

As the Libyan government is under siege and migratory routes to Europe are redrawn, the London-based Institute for International Center for Relations and Diplomacy (ICRD) and the Athens-based Institute for Migration Studies (IMM, Athens) organized in Athens a seminar devoted to the toxic alignment of migration coverage and elections on Thursday, April 18, 2019.

Libya, migration, elections, and social media

The event was timely, as the Libyan war has reached a climax, changing migration routes to Europe.

Migration reporting is a seasonal phenomenon, with media attention focusing on the sea crossing from Africa to Europe during the spring and summer, when the weather allows for the perilous crossing of the Mediterranean. This year, the migration routes from North Africa to Europe are shifting, just as Europe is about to go to the polls in the May 26, 2019 European elections. The alignment of war coverage, the migration season, and elections is potentially toxic. Already, polling around Europe projects a major boost for political parties that are xenophobic and Islamophobic.

In this context, reflecting on the responsibility of the media in covering and indeed shaping public discourse is essential. The event featured the Member of Parliament and candidate for the European Parliament Spyros Danellis (Syriza, NGL/GUE), journalists, and human rights activists. The focus of their discussion is Libya and the toxic mixture of a changing migration map – triggered by the Libyan crisis – online journalism, and the countdown to the May 26 European election.

Libya & Redirecting the route to Europe

On behalf of ICRD, Sophia Akram sketched the experience of refugee and migrant flows that due to the conflict are diverted from Libya to the Tunisian desert, Egypt, or Turkey and Greece. The new migration map emerges as the weather improves, allowing those on the move to attempt the perilous journey across the Mediterranean. That is the last leg of a voyage from Sub-Saharan Africa that is often the most dangerous and many will not make it across.

Reflecting on her own experience as a journalist, Akhram talked about the difficulty of pitching to the editors empathy with the plight of those making the journey, contrasting this difficulty with the appeal of using migration to excite fear and stimulate digital online engagement with stories of invasion. “YouTube, Facebook, and other social media platforms have been instrumental in creating political capital for prominent figures of the European right, like Matteo Salvini in Italy and Nigel Farage in the UK.”

Selling fear

Picking up on that note, Spyros Danelis, recalled the main campaign motto of the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party “We must not become Euro-Arabia.” Danellis focused on the political significance and indeed effectiveness of fear in politics, especially of migration, allowing campaigners to point to a single cause for a cluster of existing social challenges – unemployment, inequality, declining social services – and offer themselves as protectors of the public.

In this context “media do not merely reflect but actually construct a reality,” Danelis noted, making the case that “in view of the far-right Matteo Salvini and a polarized media landscape that divides the world between ‘us and them,’ political forces that consider themselves progressive – and editorially responsible media platforms – have a responsibility to reshape the way we perceive and talk about migration and refugees.”

On the point of “constructing reality,” the journalist Giannis Pandelakis and author of the best selling book “The Lost Honour of Journalism,” pointed to patterns of dissemination of fake news in local media and peer-to-peer social media channels that work in synergy with far-right politics.

The main problem with fear politics is that it works, Pandelakis explained. “Fear sells, as we see across Europe, as parties that invest in fear see their electoral returns well; {and} because fear is effective it also contaminates the language of so-called mainstream parties.”

From left to right: Dimitris Levantis, Giannis Pandelakis, Spyros Danellis, Theodoros Benakis and Sophia Akram.

From left to right: Dimitris Levantis, Giannis Pandelakis, Spyros Danellis, Theodoros Benakis and Sophia Akram.

Fear is an effective media force because it motivates engagement and dissemination, which is where the value really is in digital journalism. In this context, he offered a number of anecdotal “fake news” rumors about migrants and refugees, especially Moslems, that spread like fire in localities across Greece during the 2015 refugee crisis: refugees were reported as eating dogs, organizing orgies, demanding that bells to not sound on Sundays because they are Muslim, as receiving pensions and handouts that do not exist, and so forth.

“In 2015, the media were not reporting reality but creating reality and dissenting views were either treated with fury but, worse yet, drowned in silence and oblivion because anger is more effective in triggering engagement.”

Drowning solidarity in oblivion

Dwelling deeper in the realities of social media engagement, the human rights lawyer and activist of Catholic NGOs, Dimitris Levantis, focused his attention on the oblivious attitude of media coverage towards charity and solidarity.

“Children from Syria have filled the schools that no longer have Greek children,” noted Dimitris Levantis, focusing on the underreporting of how refugee children mainly from the Middle East added joy in ever-smaller Greek schools, which close down due to immigration and demographic stagnation.

“I am proud that the Greek educational system was able to fill the schools, stop underage marriage to some extent, and helped Greece that is suffering itself from demographic stagnation,” Levandis noted.

He also noted other ways in which media frames reality.

“It is interesting that foreign investors are never referred to as migrants; what really triggers our anger is the poverty of the newcomers,” Levandis added.

Referring to his experience in faith-based Christian solidarity organizations in Europe, he drew attention to the work of the Lutheran Church in the Netherlands and the Catholic Church in Italy, who are drawing anger for preaching solidarity and taking action in solidarity with refugees. “We lose members of our congregation,” he was told by a Lutheran activist, “but we will regain them,” he said with confidence.