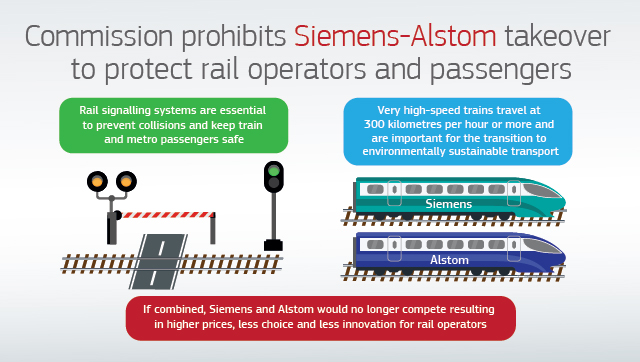

The European Commission has prohibited Siemens’ proposed acquisition of Alstom under the EU Merger Regulation. The merger would have harmed competition in markets for railway signalling systems and very high-speed trains. The parties did not offer remedies sufficient to address these concerns.

“Millions of passengers across Europe rely every day on modern and safe trains. Siemens and Alstom are both champions in the rail industry. Without sufficient remedies, this merger would have resulted in higher prices for the signalling systems that keep passengers safe and for the next generations of very high-speed trains. The Commission prohibited the merger because the companies were not willing to address our serious competition concerns,” said Commissioner Margrethe Vestager, in charge of competition policy.

Today’s decision follows an in-depth investigation by the Commission of the takeover, which would have combined Siemens’ and Alstom’s transport equipment and service activities in a new company fully controlled by Siemens. It would have brought together the two largest suppliers of various types of railway and metro signalling systems, as well as of rolling stock in Europe. Both companies also have leading positions globally.

According to European Commission’s press release the merger would have created the undisputed market leader in some signalling markets and a dominant player in very high-speed trains. It would have significantly reduced competition in both these areas, depriving customers, including train operators and rail infrastructure managers of a choice of suppliers and products.

The Commission received several complaints during its in-depth investigation, from customers, competitors, industry associations and trade unions. It also received negative comments from several National Competition Authorities in the European Economic Area (EEA).

Stakeholders were worried that the proposed transaction would significantly harm competition and reduce innovation in signalling systems and very high-speed rolling stock, lead to the foreclosure of smaller competitors and to higher prices and less choice for customers. Since the parties were not willing to offer adequate remedies to address these concerns, the Commission blocked the merger to protect competition in the European railway industry.

The creation of a genuine European railway market depends crucially on the availability of signalling systems, which are compliant with the European Train Control System (ETCS) standard at competitive prices. Investment in signalling systems that comply with this standard will allow trains to operate safely and smoothly across borders between Member States. New investments in trains are key to transition to more climate friendly and environmentally sustainable mobility.

The Commission’s concerns

The Commission had serious concerns that the proposed transaction would significantly impede effective competition in two main areas: (i) signalling systems, which are essential to keep rail and metro travel safe by preventing collisions,and (ii) very high-speed trains, which are trains operating at speeds of 300 km per hour or more.

More specifically, the Commission’s investigation showed that:

For signalling systems, the proposed transaction would have removed a very strong competitor from several mainline and urban signalling markets.

o The merged entity would have become the undisputed market leader in several mainline signalling markets, in particular in ETCS automatic train protection systems (including both the systems installed on-board a train and those placed along the tracks) in the EEA and in standalone interlocking systems in several Member States.

o In metro signalling, an essential element of metro systems, the merged entity would also have become the market leader in the latest Communication-Based Train Control (CBTC) metro signalling systems.

For very high-speed rolling stock, the proposed transaction would have reduced the number of suppliers by removing one of the two largest manufacturers of this type of trains in the EEA. The merged entity would hold very high market shares both within the EEA and on a wider market also comprising the rest of the world except South Korea, Japan and China (which are not open to competition). The merged entity would have reduced competition significantly and harmed European customers. The parties did not bring forward any substantiated arguments to explain why the transaction would create merger specific efficiencies.

In all of the above markets, the competitive pressure from remaining competitors would not have been sufficient to ensure effective competition.

As part of its investigation, the Commission also carefully considered the competitive landscape in the rest of the world. In particular, it investigated the possible future global competition from Chinese suppliers outside of their home markets:

As regards signalling systems, the Commission’s investigation confirmed that Chinese suppliers are not present in the EEA today, that they have not even tried to participate in any tender as of today and that therefore it will take a very long time before they can become credible suppliers for European infrastructure managers.

As regards very high-speed trains, the Commission considers it highly unlikely that new entry from China would represent a competitive constraint on the merging parties in a foreseeable future.

The parties’ proposed remedies

Remedies proposed by merging companies must fully address the Commission’s competition concerns on a lasting basis. Where concerns arise because of loss of direct competition between the merging companies, remedies providing a structural divestiture are generally preferable to other types of remedies. This is because they immediately replace the competition in the markets, which would have been lost from the merger. These types of structural solutions were offered by parties and accepted by the Commission in past mergers such as BASF’s acquisition of Solvay’s nylon business, Gemalto’s acquisition by Thales, Linde’s merger with Praxair, GE’s acquisition of Alstom’s power generation and transmission assets or Holcim’s acquisition of Lafarge.

However, in this case, the remedies offered by the parties did not adequately address the Commission’s competition concerns. In particular:

In mainline signalling systems, the remedy proposed was a complex mix of Siemens and Alstom assets, with some assets transferred in whole or part, and others licensed or copied. Businesses and production sites would had to be split, with personnel transferred in some cases but not others. Moreover, the buyer of the assets would have had to continue to be dependent on the merged entity for a number of licence and service agreements. As a result, the proposed remedy did not consist of a stand-alone and future proof business that a buyer could have used to effectively and independently compete against the merged company.

In very high-speed rolling stock, the parties offered to divest a train currently not capable of running at very high speeds (Alstom’s Pendolino), or, alternatively, a licence for Siemens’ Velaro very high-speed technology. The licence was subject to multiple restrictive terms and carve-outs, which essentially would not have given the buyer the ability and incentive to develop a competing very high-speed train in the first place.

The Commission sought the views of market participants about the proposed remedy. The feedback was negative for both areas.

This confirmed the Commission’s view that the remedies offered by Siemens were not enough to address the serious competition concerns and would not have been sufficient to prevent higher prices and less choice for railway operators and infrastructure managers.

As a result, the Commission has prohibited the proposed transaction.